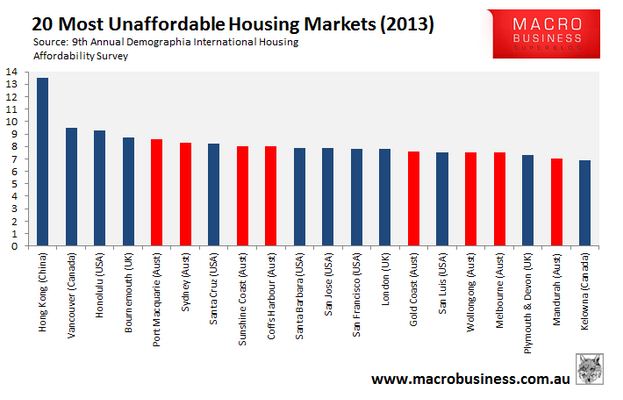

Australia still has one of the most expensive housing markets in the world, according to the 9th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

And, according to this survey, Port Macquarie ranks as the world's fifth most unaffordable housing market. the only places in the world ranked worse are Hong Kong, Vancouver, Honolulu and Bournemouth, UK.

|

This year's report assesses 337 markets in seven countries: Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Ireland, New Zealand, Britain and the US.

* More in Wednesday's Port News

A recent survey spells bad news for housing affordability. APM's Andrew Wilson disagrees.

The survey ranks urban markets into four categories from “affordable” (3.0 or less) to “severely unaffordable” (5.1 or more).

According to the survey, median multiples were historically 3.0 or less in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, Britain and the US, a notion supported by research at the Reserve Bank.

While this affordability relationship is present in many housing markets of the US, Canada and Ireland, the median multiple has escalated sharply in the past decade in the other housing markets.

Of the 337 markets surveyed, a significant proportion of the unaffordable ones are in Australia, with 30 ranked as severely unaffordable and nine seriously unaffordable.

Australia has none ranked as affordable or moderately unaffordable. Last year's survey contained only 25 markets in the severely unaffordable category.

The increase is due to an expansion of the survey's coverage to a number of mining localities in Western Australia and Queensland.

Overall, Australia has moved down the tables, registering eight out of the 20 most expensive markets identified, but only four in the top 10, compared with five last year.

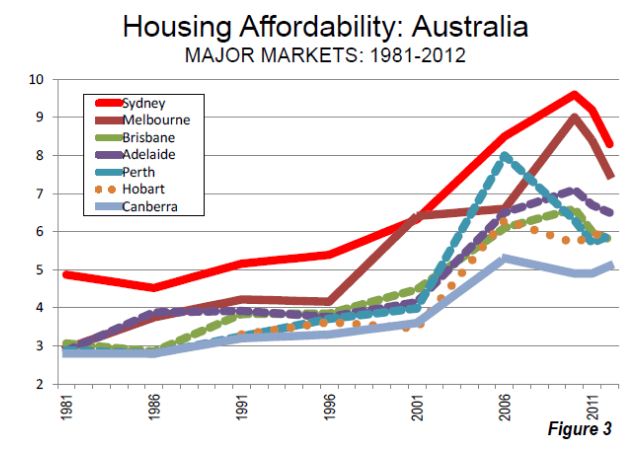

The overall decline in affordability in Australia – and the modest recent improvements – are clear.

|

Whereas all big Australian markets except Sydney had median multiples of three in the early 1980s, today all are ranked about five or above.

The survey concludes that higher land prices are the main contributor to the rapidly increasing prices in unaffordable markets. The land costs include the increasing influence of land supply restrictions, such as urban growth boundaries, excessive infrastructure fees and other overly strict land use regulations.

Overwhelming economic evidence indicates that urban containment policies, especially growth boundaries, raise the price of housing compared to income. This inevitably leads to a reduced standard of living and increases poverty rates, because the unnecessarily higher costs of housing leave households with less discretionary income to spend on other goods and services.

The higher costs ripple into rental markets, tightening the budgets of lower-income households, which already suffer from lower discretionary incomes.

The main problem is the failure to maintain a "competitive land supply".

An economist at Brookings Institution, Anthony Downs, says more urban growth boundaries can give monopolistic pricing power to sellers if insufficient land is available, which is likely to raise the price of land and housing built on it.

Urban containment policy has been associated with greater price volatility and speculation. Investors and speculators are drawn to metropolitan areas where "quick" money is to be made, because of the inflexibility of the supply market.

In the 2011 survey, Demographia noted that in Australia, 95 per cent of the rise in inflation-adjusted new house (and land) costs were attributable to land, rather than construction from 1993 to 2006.

In San Diego, which is more regulated, house prices were 250 per cent higher than in Dallas-Fort Worth in 2007, yet cost only 15 per cent more to build.

Demographia's contention that Australia's rising prices have been caused mainly by escalating land costs is supported by all capital city markets experiencing strong growth in vacant land values in the decade to 2012, according to RP Data.

Demographia argues the key reason for this land price escalation in Australia (as well as in New Zealand, Britain and the expensive markets of the US and Canada) is that the market's ability to quickly provide low-priced new housing is hampered by restrictive land use regulations, many of which have come into effect since the mid-1990s. (Sydney has long had limits on housing development on the urban fringe.)

But restrictive urban planning structures should not be viewed as a one-way bet for house prices.

Demographia notes that unresponsive land supply is more likely to result in higher levels of house price volatility and boom-bust price cycles, because strict land-use planning steepens the supply curve, which makes house prices more sensitive to changes in demand, increasing the likelihood of the housing market experiencing boom-bust price cycles as demand rises or falls.

Leith van Onselen is an economist formerly with the Australian Treasury and Goldman Sachs. His full report is available at MacroBusiness.

Leith van Onselen is an economist formerly with the Australian Treasury and Goldman Sachs. His full report is available at MacroBusiness.

Leith van Onselen is an economist formerly with the Australian Treasury and Goldman Sachs. His full report is available at MacroBusiness.